The past 12 months have been extremely productive for MAP, with some major successes and milestones to celebrate! The accomplishments below are thanks to our world-class team of researchers, staff and students; our partnerships with the communities we study; and our incredible donors, without whom our work would simply not be possible. I also want to thank Staples Canada leadership and associates for another very successful year of our Even the Odds partnership. Staples’ commitment and vision have been truly transformative for our centre.

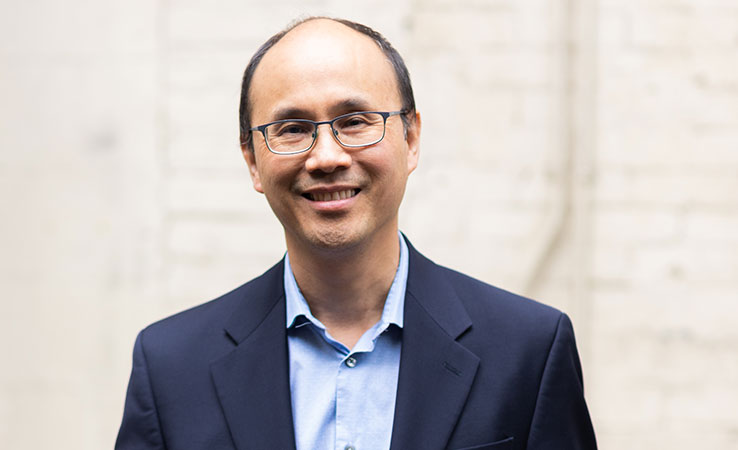

This year, MAP celebrated 25 years since our founding as a tiny, one-scientist hospital unit in 1998. It has been an interesting and inspiring opportunity to reflect on our history as a centre. Recently, I had the opportunity to sit down with Jeff Lozon and Ahmed Bayoumi to reflect on MAP’s beginnings, and in particular what it meant to embed an equity-focused research centre within St. Michael’s Hospital. It was a fascinating discussion – listen here.

As we look forward to another year of growth, progress and (as always) new challenges, the imperative remains: in 2024 and beyond, we must continue to work together towards a healthier future for all. Thank you for your interest in MAP’s work, and commitment to our vision.

Sincerely,

Dr. Stephen Hwang

Director, MAP Centre for Urban Health Solutions

Chair, Homelessness, Housing and Health, St. Michael’s Hospital, Unity Health Toronto

2023 Research Highlights

? MAP conducts largest-ever public consultation on primary health care: Over the past 16 months, MAP scientist Dr. Tara Kiran convened thousands of people across Canada to share their perspectives and consider new possibilities for primary care in Canada. The results are captured in five priorities panel reports, 10 population-specific roundtable reports (coming soon), and a public website of national survey data. All findings will come together in 2024 in a concrete and achievable vision for a stronger, more equitable, and effective primary care system in Canada – a system that works for everyone.

⚕️ Vending machines that dispense free HIV test kits, safe-injection supplies and Naloxone begin rollout across Canada: Even the Odds and MAP launched the first Our Healthbox vending machines in Atlantic Canada, followed by implementation in Ontario. More than 1,500 people have since used the machines to access the things they need for their health, including 400 HIV self-testing kits – many for people who had never been tested before. MAP scientist and Healthbox lead Dr. Sean B. Rourke has set an ambitious goal to roll out 100 Healthboxes across Canada by 2026 to help address the overdose crisis and remove barriers to HIV testing and care.

? MAP scales up opioid crisis response with new funding from Health Canada, partnership with NIH: Health Canada announced that MAP’s Drug Checking Service will be part of an expanded drug strategy to tackle the opioid crisis, with $2M funding to scale up the service across Ontario. Led by MAP’s Karen McDonald, the Toronto service checked more than 3,500 samples in 2023, and more than 11,000 samples since the program launched in 2019. Dosecheck, MAP’s emerging drug checking technology, also received new funding from Health Canada and kicked off an innovative partnership with NIH to accelerate its development.

? A comprehensive new set of guidelines to promote health equity in Canada: MAP scientists Dr. Nav Persaud and Dr. Aisha Lofters published new recommendations in CMAJ to improve health care for people who face barriers in accessing it, including people who are Indigenous, racialized, 2SLGBTQ+, as well as those who live with functional limitations or low incomes. The paper garnered more than 550 media hits, making it one of CMAJ’s top covered articles in 2023. MAP also released an accompanying online tool that patients and care providers can use to guide preventative care and screening decisions: screening.ca.

? MAP’s Navigator Project expands to BC: Thanks to Even the Odds funding, MAP’s Navigator Project continues to scale up with a new site at St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver. The innovative program pairs patients who are homeless with an outreach worker to connect them to care, ensure a better recovery, and potentially reduce readmission to hospital. In addition to St. Paul’s, Navigator is currently operating at St. Michael’s Hospital and St. Joseph’s Health Centre in Toronto, with plans to launch in Montreal in 2024.

? New app offers 24/7 support to people with gambling concerns: MAP scientist Dr. Flora Matheson’s SPRinG app is a free journaling and tracking tool that helps users understand their gambling patterns and urges. Designed in partnership with community groups and people who have experienced problem gambling, the app has more than 250 users and is being rolled out in Playsmart Centres across Ontario. This year, Dr. Matheson’s research team also launched gamblingandpoverty.ca to share evidence and information on the strong, concerning links between homelessness and problem gambling.

? A call for a national inquiry into Canada’s COVID-19 ‘failures’: MAP scientist Dr. Sharmistha Mishra co-authored a series of papers in the British Medical Journal that explored Canada’s successes and failures re: COVID-19 pandemic response. Dr. Mishra emphasized that Canada’s successes, such as high vaccination rates, often overshadow the geographical, social and economic COVID inequities across the country. Media coverage included The Toronto Star, CTV News and an opinion piece in the Globe & Mail.

❄️ Policy impact: Toronto increases temperature threshold for activating warming centres: In their 2023/2024 Winter Services Plan, The City of Toronto raised the warming centre threshold from -15C to -5C. Although there is still more work to be done, the Toronto Star attributes this positive change to a 2019 MAP study that showed that most cases of cold-related injury and death in Toronto happen in moderate winter weather. MAP Director Dr. Stephen Hwang and MAP scientist Dr. Carolyn Snider also gave powerful deputations to the City of Toronto in early 2023, urging the city to take stronger action in protecting the health and wellbeing of unhoused people in Toronto this winter.

? MAP hosts second Solutions for Healthy Cities Symposium: On March 23, MAP gathered almost 200 researchers, service providers, policymakers, students and community experts to explore and discuss this year’s symposium theme, The Science and Practice of Implementation Success. Step by step, each learning session walked participants through a stage of the Active Implementation Framework, illustrated by presenters’ real-life experiences, challenges and lessons learned.

? “A game changer”: Dual HIV-Syphilis rapid test approved for use in Canada: Federal regulators have approved an all-in-one rapid device that allows people in Canada to be simultaneously tested for HIV and syphilis, and get their results in as little as 60 seconds. The approval was made possible, in part, by the results of a two-year clinical trial led by MAP scientist Dr. Sean B. Rourke and researchers at the University of Alberta. The test will be a crucial tool in the fight against a recent, alarming increase in babies born with congenital syphilis – particularly in Canada’s prairie provinces.

? APPLE Schools expands to five new elementary schools: APPLE Schools is an internationally recognized best practice that has been proven to help kids move more, eat better, and feel happier – erasing many of the long-term health effects of childhood poverty. In 2023 Dr. Katerina Maximova, MAP’s Murphy Family Foundation Chair in Early Life Interventions, brought the program to five new elementary schools in Ontario. Since September 2022, MAP and Even the Odds have implemented and begun evaluation of the program at 15 schools in total (Ontario and Alberta), reaching more than 4,500 students.

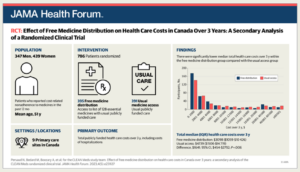

? MAP research continues to strengthen the case for universal pharmacare: MAP’s CLEAN Meds study published startling new findings: providing prescriptions free of charge to patients saves the public health care system an average of $1,488 per patient per year by helping to prevent unexpected trips to the hospital, ED visits and other avoidable health care costs. These findings and others from MAP scientist Dr. Nav Persaud’s CLEAN Meds trial continues to strengthen and advance the case for universal pharmacare, and a federal commitment may be on the horizon.

?️ Education to help end ‘race correction’ in health care: In partnership with the Canada-US Coalition to End Race Correction and the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, MAP helped to present the education series Ending “Race Correction” in Health Care, which explores the ways that Black people are systematically excluded from timely access to diagnoses and treatment. To date, more than 3,000 people including clinicians, medical students and researchers from universities, clinics and hospitals in a range of jurisdictions have watched the talks, including a presentation on what race correction means for systematic reviews and research.

Want more research updates?

Subscribe to MAP’s Junction e-newsletter for short, monthly updates on our studies, our solutions, and the issues we study. You can also follow MAP on Twitter and LinkedIn, and subscribe to our MAPmaking podcast.