Closing the gender pay gap in medicine in Canada requires a multipronged approach to overcome systemic bias, including payment and hiring transparency, changes to medical education, better parental leave and more, as outlined in an analysis article in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal).

In Ontario, male family physicians earn 30% more, and male specialists earn 40% more than their female counterparts on average.

“The gender pay gap exists within every specialty and also between specialties, with physicians in male-dominated specialties receiving higher payments,” write Dr. Tara Kiran, St. Michael’s Hospital of Unity Health Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, and Dr. Michelle Cohen, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario. “The gap in not explained by women working less but, rather, relates more to systemic bias in medical school, hiring, promotion, clinical care arrangements, mechanisms used to pay physicians and societal structures more broadly.”

Research from the United States and the United Kingdom indicates that the pay gap persists after adjusting for physician age, specialty, number of hours worked and other factors. In Canada, the proportion of female physicians has grown from 11% in 1978 to 43% in 2018, but women make up only 8% of Ontario’s highest billing physicians.

“Women in medicine face discrimination throughout their careers,” the authors write. “This discrimination is rooted in the history of women’s exclusion from the profession, along with the institutional legacies of sexism in medical schools, clinical care arrangements, health organizations and the fee system itself. In the early stage of their careers, the ‘hidden curriculum’ both subtly and overtly encourages women trainees to enter specific, often lower-paid, specialties.”

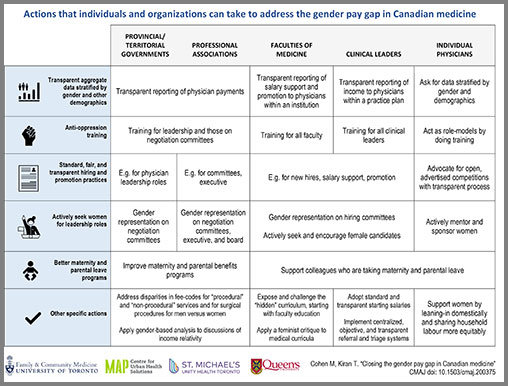

Provincial and territorial governments, institutions and faculties of medicine, professional associations, clinical leaders and individual physicians all have a role to play.

Actions to close the pay gap include:

- Transparent data, including reporting of physician payments by gender and other demographic characteristics

- Antioppression training for leadership

- Addressing gender bias in medical schools and medical curricula

- Standard, fair, and transparent hiring and promotion practices

- Actively seeking and encouraging women for leadership roles

- Better maternity and parental leave programs

“[W]ork to address gender pay equity in medicine cannot be done in isolation,” write the article’s authors. “The medical profession should remain mindful of the relative privilege of physicians in society and support advances for women struggling in precarious, lower-paid work; solutions for the medical profession should not exacerbate broader societal income inequality. Efforts to close the gender pay gap in medicine should embrace efforts to measure and reduce pay gaps related to other intersecting forms of discrimination, including race and disability.”

Listen to the CMAJ podcast interview with Drs. Kiran and Cohen: https://soundcloud.com/cmajpodcasts/200375-ana