How can we deliver quality diabetes care in a virtual environment?

Members of the Division of Endocrinology at St. Michael’s recognized right away that the virus, the public health interventions and the new methods of care delivery would impact people who live with diabetes.

For example, preliminary reports suggested that people with diabetes are at higher risk of dangerous outcomes of COVID-19, such as requiring critical care or ventilation.

Dr. Gillian Booth, Dr. Andrew Advani and Dr. Catherine Yu – three endocrinologists with different research focuses – launched the CONNECT study – short for COVID-19 and Diabetes: Clinical Outcomes and Navigated NEtwork Care Today.

“There was a lot of worry, fear and uncertainty amongst people with diabetes,” said Dr. Advani, who is also a researcher at the Keenan Research Centre for Biomedical Science. “Social distancing measures were introduced and persons with diabetes didn’t have the usual face-to-face contact with their usual support network that is critical for effective self-management.”

The CONNECT study aims to address these potential gaps. It has two parts and involves physicians in the Department of Medicine, researchers at the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute (LKSKI), a diabetes educator, a social worker, people living with diabetes, and researchers from other Toronto hospitals.

The first part addresses the risk of developing COVID-19 for those who are living with diabetes.

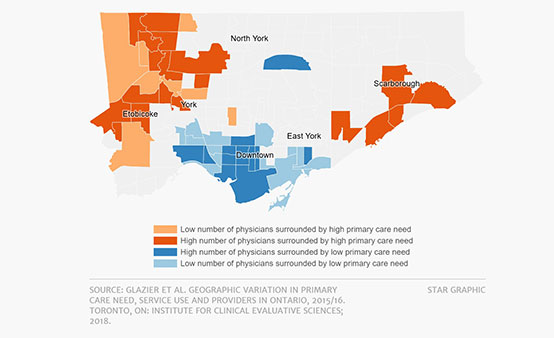

“We get a lot of questions from our patients about this,” said Dr. Booth, who is also a scientist at the MAP Centre for Urban Health Solutions. “Using large databases of hospital admissions, we aim to answer this question for our patients of whether diabetes really is a risk factor for poor outcomes from COVID-19 in Canada and, if so, what causes this increased risk.”

The team also hopes to learn whether fear of the virus stopped people with diabetes from accessing emergency care when they needed it. This information, the researchers say, will be useful to prepare for potential future waves of the virus.

The second part involves interviewing patients living with diabetes to learn how to make sure virtual care strategies make sense for them.

“By listening to patient voices, we hope to be able to continually improve the care of persons with diabetes,” said Dr. Catherine Yu, who is also a scientist at the LKSKI. “We hope that, by sharing these experiences, we will be able to help other health-care providers improve the care that they provide too.”

The research team is recruiting team members and aims to work with patients soon.

“It’s clear that virtual care is likely to be part of the fabric of the way health-care is delivered in the future,” Dr. Advani said. “It’s been a steep learning curve and we are all continuing to learn. If some type of virtual care is going to stay with us, we need to learn what works best for health-care providers, patients and their families so that we can deliver the best care, with the best patient experiences and the best outcomes.”