From Unity Health Toronto

Unity Health Toronto welcomed Ya’ara Saks, Minister of Mental Health and Addictions, Marci Ien, Minister for Women and Gender Equality and Youth of Canada, and Dr. Leigh Chapman, Chief Nursing Officer of Canada, to St. Michael’s Hospital on Oct. 30 to announced more than $21 million in funding for 52 projects to address the toxic drug and overdose crisis.

The funding was provided through Health Canada’s Substance Use and Addictions Program (SUAP) – and included money for Toronto’s Drug Checking Service, housed at St. Michael’s Hospital, and the emerging drug checking technology DoseCheck.

Toronto’s Drug Checking Service is a community-based public health service that allows people to submit a sample of their drug to be tested and receive results about what’s in it, along with tailored strategies to reduce harm and referrals to drug-related, health and social services.

The program also combines results to perform unregulated drug market monitoring and shares this information publicly every other week to inform those who cannot directly access the service, advocacy efforts, policy, and research.

“Over the past four years, my team has observed firsthand the positive and quantifiable impact drug checking services have on responding to Canada’s toxic drug supply crisis,” said Karen McDonald, Lead of Toronto’s Drug Checking Service.

“This support from Health Canada’s [SUAP] for Toronto’s Drug Checking Service and emerging drug checking technologies, like DoseCheck, will improve access to these potentially life-saving services, promote provincial monitoring of the unregulated drug supply, and, most importantly, contribute to bettering the lives of Ontarians who use drugs.”

Between January 2016 and March 2023, there were 38,514 suspected opioid overdose deaths across Canada, according to the latest federal government data.

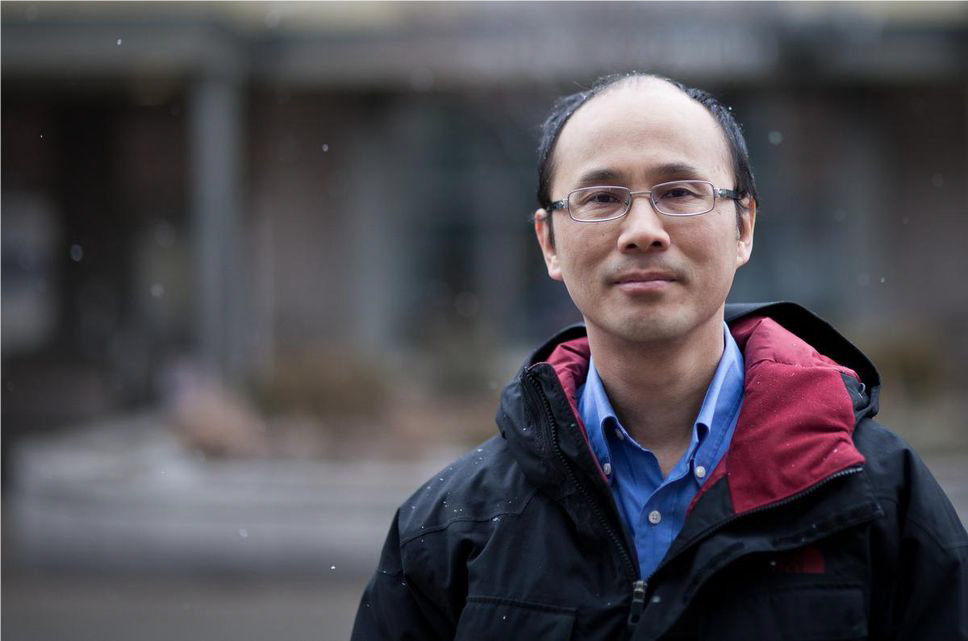

“Canada is eight years into an overdose crisis that is leading to more deaths, driven primarily by fentanyl and other high-potency opioids, and the numbers are going the wrong way and exacerbated by the pandemic,” said Dr. Dan Werb, Director of the Centre on Drug Policy Evaluation and co-creator of DoseCheck.

“All Canadians should be able to arm themselves with life-saving information about the toxic compounds circulating in the drug supply. We hope DoseCheck can help do just that.”

DoseCheck, a handheld device that connects to a free smartphone app, is designed to allow anyone anywhere to rapidly test their drug samples with no training required. It was developed in partnership with community health centers, people who use drugs, and government agencies like the U.S. National Institutes of Health and SUAP.

Minister Saks said the funding was part of the renewed Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy, and that the federal government recognizes the tragic toll the overdose crisis and other substance use related harms are taking on families, friends and communities across Canada.

“We are supporting community organizations who have deep roots in their communities, have the trust of their clients and have the first-hand knowledge needed to make a real difference in people’s lives,” she said.

“We are using every tool at our disposal to end this crisis and build a safer, healthier and more caring future for all Canadians.”