Toronto and several municipalities have declared intimate partner violence an epidemic. In this op-ed Dr. Patricia O’Campo, along with Allison Branston and Thea Symonds, call upon other municipalities to do the same. They also share the innovative work their team is doing in collaboration with social services, shelters, and criminal justice providers to safely house women and children experiencing violence.

Author: Samira Prasad

Brampton mayor urges federal help after asylum claimant death

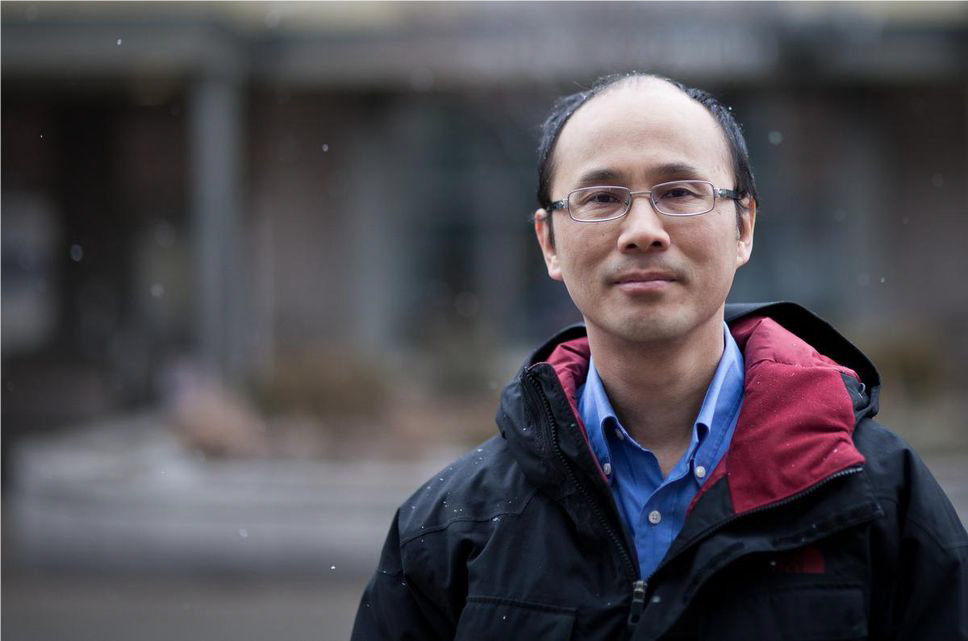

Brampton Mayor, Patrick Brown is demanding Ottawa help after an asylum claimant camped outside a shelter was found dead Wednesday morning. Dr. Stephen Hwang spoke with Humber News about how governments need to consider both short-term and long-term solutions.

The article also reports that the city’s winter readiness plan changed its warming centres to open at -5 C instead of at the -15 C extreme cold weather alert threshold. The decision was made in part because of a 2019 report from the MAP Centre for Urban Health Solutions which found that 72 per cent of hypothermia cases in adults experiencing homelessness from 2004 to 2015 occurred when temperatures were warmer than -15 C.

How a new ‘super screener’ is helping detect cancer in patients without a family doctor

Dr. Tara Kiran spoke to The Globe and Mail about the importance of primary care access and about how people who don’t have family doctors are missing out on more than just cancer screening.

New smart vending machine in Ottawa revolutionizes access to essential supplies

Dr. Sean Rourke spoke with CTV News about the new Healthbox machine at the Carlington Community Health Centre in Ottawa, the first of its kind in Ontario.

‘We are so incredibly relieved’: Toronto’s drug checking pilot gets greenlight to expand

CBC News spoke with MAP scientist Dr. Tara Gomes and Toronto’s Drug Checking Services‘ lead Karen McDonald about plans to expand the program and offer existing services throughout the province.

“The federal government says the service will help groups across the province design and execute their own drug checking programs, with the original team acting as a “central repository” for the data generated. Researchers with Toronto’s Drug Checking Service will then analyze the data, helping to paint a fuller picture on how unregulated drug supply trends are playing out across the province and comparing them to the rest of the country.“

Cocaine use rising in Canada, new data suggests, as researchers link stimulants to drug deaths

Dr. Tara Gomes recently spoke with CBC about a recent report showing a drastic increase in deaths related to multiple toxic substances, including stimulants.

Health Canada funds 2 key drug checking projects at St. Michael’s Hospital

Unity Health Toronto welcomed Ya’ara Saks, Minister of Mental Health and Addictions, Marci Ien, Minister for Women and Gender Equality and Youth of Canada, and Dr. Leigh Chapman, Chief Nursing Officer of Canada, to St. Michael’s Hospital on Oct. 30 to announced more than $21 million in funding for 52 projects to address the toxic drug and overdose crisis.

The funding was provided through Health Canada’s Substance Use and Addictions Program (SUAP) – and included money for Toronto’s Drug Checking Service, housed at St. Michael’s Hospital, and the emerging drug checking technology DoseCheck.

Toronto’s Drug Checking Service is a community-based public health service that allows people to submit a sample of their drug to be tested and receive results about what’s in it, along with tailored strategies to reduce harm and referrals to drug-related, health and social services.

The program also combines results to perform unregulated drug market monitoring and shares this information publicly every other week to inform those who cannot directly access the service, advocacy efforts, policy, and research.

“Over the past four years, my team has observed firsthand the positive and quantifiable impact drug checking services have on responding to Canada’s toxic drug supply crisis,” said Karen McDonald, Lead of Toronto’s Drug Checking Service.

“This support from Health Canada’s [SUAP] for Toronto’s Drug Checking Service and emerging drug checking technologies, like DoseCheck, will improve access to these potentially life-saving services, promote provincial monitoring of the unregulated drug supply, and, most importantly, contribute to bettering the lives of Ontarians who use drugs.”

Between January 2016 and March 2023, there were 38,514 suspected opioid overdose deaths across Canada, according to the latest federal government data.

“Canada is eight years into an overdose crisis that is leading to more deaths, driven primarily by fentanyl and other high-potency opioids, and the numbers are going the wrong way and exacerbated by the pandemic,” said Dr. Dan Werb, Director of the Centre on Drug Policy Evaluation and co-creator of DoseCheck.

“All Canadians should be able to arm themselves with life-saving information about the toxic compounds circulating in the drug supply. We hope DoseCheck can help do just that.”

DoseCheck, a handheld device that connects to a free smartphone app, is designed to allow anyone anywhere to rapidly test their drug samples with no training required. It was developed in partnership with community health centers, people who use drugs, and government agencies like the U.S. National Institutes of Health and SUAP.

Minister Saks said the funding was part of the renewed Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy, and that the federal government recognizes the tragic toll the overdose crisis and other substance use related harms are taking on families, friends and communities across Canada.

“We are supporting community organizations who have deep roots in their communities, have the trust of their clients and have the first-hand knowledge needed to make a real difference in people’s lives,” she said.

“We are using every tool at our disposal to end this crisis and build a safer, healthier and more caring future for all Canadians.”

Drug checking services to be expanded across Ontario as drug-related deaths continue to rise exponentially

Toronto’s Drug Checking Service has been awarded two years of support by Health Canada’s Substance Use and Addictions Program to extend and expand the delivery of drug checking services in Ontario. Phase 2 will be led by Karen McDonald – a leader in drug checking service provision and unregulated drug market monitoring, who was responsible for designing and overseeing the program throughout its pilot period – in collaboration with the program’s member organizations. The program will remain housed within MAP Centre for Urban Health Solutions at St. Michael’s Hospital, a site of Unity Health Toronto.

Drug checking is a public health service that aims to reduce the harms associated with substance use by uncovering the contents of the unregulated drug supply. While access has remained limited within Canada, drug checking services in Toronto, across British Columbia, and elsewhere, have had a positive and quantifiable impact on responding to Canada’s toxic drug supply crisis. For example, drug checking:

- Provides potentially life-saving information to those at highest risk of overdose

- Facilitates behaviour change that reduces the risk of overdose

- Provides a new gateway to accessing harm reduction services

- Provides the only source of real time monitoring and public dissemination of unregulated drug market trends

- Provides data that informs clinicians and care and improves health and social services

- Is valuable to people who use drugs, empowering them to advocate for themselves and help develop solutions that impact them.

The pilot program for Toronto’s Drug Checking Service launched in October 2019 within Dr. Dan Werb’s Centre on Drug Policy Evaluation. Over the course of the pilot period, more than 10,000 samples from the unregulated drug supply were checked and over 450 unique drugs were identified – many of which can be directly linked to overdose. Service users, who submitted substance or used equipment samples to be checked, were provided with detailed information on the composition of their drugs, along with tailored strategies to reduce harm and referrals to drug-related, health, and social services via integrated community health agencies (Moss Park Consumption and Treatment Service, Parkdale Queen West Community Health Centre and the TRIP! Project, South Riverdale Community Health Centre, The Works at Toronto Public Health). Samples were analyzed by the clinical laboratories at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health and St. Michael’s Hospital. Beyond educating individual service users, results for all samples were collated and analyzed to perform unregulated drug market monitoring, then translated and

publicly disseminated every other week to communicate drug market trends to those who could not directly access the service, as well as to inform care for people who use drugs, advocacy, policy, and research.

Key objectives for phase 2 of the program are to:

- Improve access to drug checking in Toronto by increasing the number of sites that offer services

- Support the delivery of drug checking services in jurisdictions across Ontario by sharing tools, resources, and expertise to reduce the barriers associated with offering services while increasing health system efficiencies

- Conduct unregulated drug market monitoring for Ontario by bringing together data generated from checking samples using a variety of drug checking technologies

- Translate findings to advocate for services and safer alternatives for people who use drugs

Toronto’s Drug Checking Service has been without a long-term funding commitment since March 31, 2023. A special thank you to the St. Michael’s Hospital Foundation and Public Health Agency of Canada for their support during this period of uncertainty. Additionally, we thank the community of people who use drugs in Toronto who access our service and provide ongoing feedback to improve it, as well as our members, partners, and collaborators. We are grateful to continue to work with and serve you.

With questions or for more information, please contact:

Karen McDonald, MPPAL PMP | Lead, Toronto’s Drug Checking Service | Director, Program Development and Operations, MAP Centre for Urban Health Solutions, St. Michael’s Hospital, a site of Unity Health Toronto | kn.mcdonald@utoronto.ca

Toronto’s Drug Checking Service is a free and anonymous public health service that aims to reduce the harms associated with substance use and, specifically, to prevent overdose by offering people who use drugs timely and detailed information on the contents of their drugs. Beyond educating individual service users, results for all samples are collated and analyzed to perform unregulated drug market monitoring, then translated and publicly disseminated every other week to communicate unregulated drug market trends to those who cannot directly access the service, as well as to inform care for people who use drugs, advocacy, policy, and research. Sign up to receive reports, alerts, and other information on Toronto’s unregulated drug supply.

Quebec doesn’t know how many homeless people die every year. Why some say that needs to change

Dr. Stephen Hwang spoke to CBC about the importance of collecting data about deaths amongst unhoused people. “You can’t fix the problem if you don’t know how big the problem is and you don’t measure it,” he said.

Canada expands drug strategy to prevent more overdoses, provide additional services

MAP’s Toronto Drug Checking Service was featured in The Canadian Press’ piece on Canada’s recently expanded drug strategy on the overdose crisis. The project has received $2 million over two years from Health Canada as part of this strategy.